Worcester Business Journal

November 2024

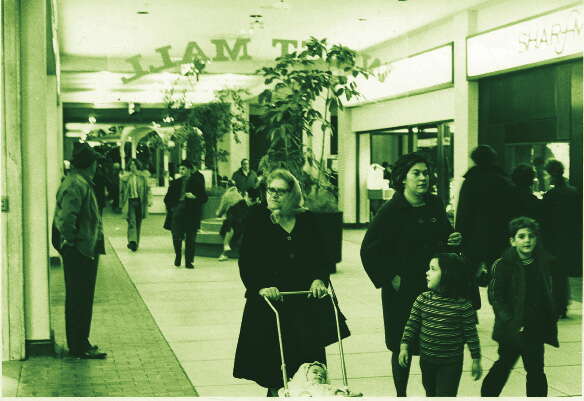

The Worcester Center Galleria came at a time when malls dominated the retail landscape.

It was 1971. Downtowns across the country were slowly dying, and Worcester in particular needed something different – something that would bring people from the region and beyond back to the center of the city. Thirty-four acres were cleared, leveling homes and businesses to make way for a brand-new, state-of-the-art indoor shopping center.

By the 1980s, though, people were already asking what would become of the downtown shopping center.

“[In the early 20th century], downtowns were the central business districts, but they had neighbors,” said Timothy Murray, president and CEO of the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce. “There were 18-hour days, a variety of different shops that supported businesses, and people that lived there.

“When they built the Worcester Galleria, they tore down acres of a mixed-use district. That’s why it didn’t succeed or survive.”

More than 50 years later, the story of Worcester Center Galleria is well-known. Like so many of the nation’s indoor shopping centers, the Galleria slowly died over the 20 years after it opened and was replaced by the short-lived Worcester Common Fashion Outlets.

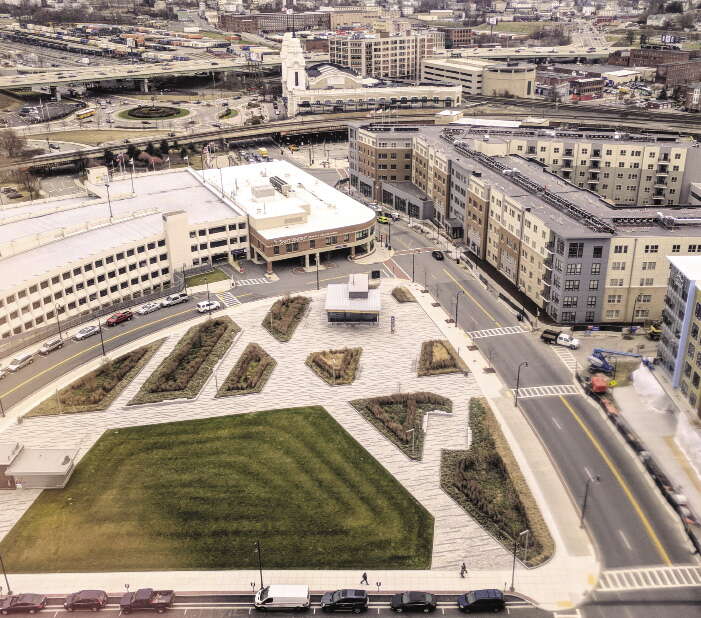

CitySquare saw the rise of the Unum Building, now rebranded as One Mercantile and adorned with the Fallon Health logo. | Photo Courtesy of Fallon Health

Today, the former mall space is known as CitySquare, and since 2010, the city of Worcester has been working with property owners to breathe life into this mixed-use, commercial, office, residential, and parking area. So far, CitySquare includes the Saint Vincent Cancer & Wellness Center, the AC Hotel by Marriott, the 145 Front at City Square apartment complex, the former Unum building known as One Mercantile, and the Worcester Common Garage.

Also included in CitySquare is Mercantile Center, 640,000 square feet of office and retail space that includes the 100 and 120 Front St. office buildings. The 100 Front St. building bore the name of the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, the city’s daily newspaper, until the T&G signage was removed last year.

Charles “Chip” Norton Jr., president and owner of Franklin Realty Advisors in Wellesley Hills, is the developer of Mercantile Center. He owns the 100 and 120 Front St. buildings, and in 2022 sold the property containing The Mercantile restaurant for $5.55 million. Norton had invested about $4.7 million to develop the space.

Both Front Street office buildings are at 95 percent occupancy or above, Norton said. The real challenge at this point is filling the remaining 50,000-60,000 square feet of retail space.

“We are starting to look at a micro-market sort of concept, but we’re not sure if the market is ready for it yet, like it would be if there were some more downtown residential,” Norton said. “We’ve talked to some retail developers to come in and take that part of the deal. They just don’t think the market is there yet.”

The Mall As It Was

The Galleria came alive in 1971, amid a nationwide shopping mall boom in the latter half of the 20th century. Downtowns were the go-to retail centers in the early 1900s, because of the proximity to bustling neighborhoods, but after World War II people started moving out to the suburbs, creating the need for shopping closer to growing residential areas, said Karl Seidman, an economic development consultant who retired from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Cities responded at first, Seidman said, by trying to be more like suburbs. Highways like Interstate 290 were built in the 1970s to make it easier for people to travel back and forth, and cities like Worcester and Boston built malls in busy urban areas.

The idea of the so-called “festival marketplace” was introduced in the 1970s and 1980s; in Massachusetts, the poster child for this idea, Seidman said, is Boston’s Faneuil Hall Marketplace. In the late 1970s, the federal government introduced the Urban Development Action Grant program to fund downtown areas struggling after suburban sprawl.

The success of these various attempts at retail dominance depended on the economic context in which they happened, Seidman said.

Galleria shoppers in the mid-1970s had plenty of stores from which to choose, like Sharfmans Jewelers.

“A large mall project in downtown that doesn’t have a substantial residential base or is in an urban center that doesn’t have workers and a lot of tourists, it’s difficult to make it work if it’s dependent on getting a lot of residents around the region to head into the city to shop,” he said. “It’s always going to be more convenient for people in the suburbs to drive and park than it will be to go downtown.”

What’s There Today

After its transformation into an outlet mall in 1994, the former Galleria space found itself once again gasping for air in the early 2000s. By then, the Wrentham Village Outlets had opened and other shopping centers like the Greendale Mall, the Solomon Pond Shopping Center and the Auburn Mall were surrounded by areas with more homes. In 2003, Murray, then the mayor of Worcester, said it was time to explore alternate uses for the downtown mall property.

“It was both a financial and psychological anchor around the city, so there was the idea of tearing it down, recreating a logical street grid, and creating a mixed-use district,” he said.

While Murray was chief among those at the vanguard of the CitySquare movement, it was Daniel R. Benoit, an architect in the city development office, who in 1999 initially suggested connecting Washington Square and Union Station with downtown by demolishing part of the mall.

Full demolition happened in 2010. By then, the city was working with Opus Investment Management, an arm of the Hanover Insurance Group, and its development partner Leggat McCall Properties on future plans for the site.

Norton said he started developing projects in Worcester in the late 1970s and early 1980s, starting in Webster Square and including One Chestnut Place. When the Front Street buildings came across his desk, he was intrigued but backed away after an initial inspection.

He saw problems.

“When I looked at it initially, it had too much retail space available, including second-floor retail space, which I thought was going to be a non-starter,” Norton said. “Second-floor retail is tough anywhere – especially in Worcester – so I kind of backed away from it.”

A view from above: An open Front Street is a linchpin of the new CitySquare development. | Photo Courtesy of WBJ

The turning point came after a discussion with UMass Memorial Health Care, Norton said. The healthcare network already occupied space in the Norton-owned Worcester Business Center on Millbrook Street. UMass Memorial officials expressed interest in having a downtown presence, and that, Norton said, is what made him take a second look at the Front Street properties. He eventually purchased them for $33 million in 2015.

“I did a deep dive on the property, got to know it, and put an offer in on it contingent on UMass committing to 90,000-plus square feet. They signed a lease, I bought the property, and they took a big chunk of second-floor space in the old mall,” he said. “With them as the mainstay, so to speak, I moved the project forward, and it’s been very successful on the office side.”

Retail, however, is taking a bit longer than Norton said he expected. About 60,000 square feet of retail space remains at the Mercantile Center, including the former Foothills Theater space, which Norton said is his pet project. Two restaurant leases – for The Mercantile restaurant and Ruth’s Chris Steak House – were finalized before COVID hit, Norton said.

Photo Courtesy of WBJ

Can the Mercantile Center and The Mercantile Restaurant succeed where the Galleria and Worcester Common Outlets failed? Time will tell.

“We allowed the tenants to basically sit on their leases, and commence buildout and occupy once they saw light at the end of the tunnel,” he said.

Going forward, Norton said he wants to bring in some retail or restaurant tenants and find the right fit for the Foothills Theater space.

He’s thinking the theater, which has less than 400 seats, would be a good comedy club or music venue, or potentially a brew hall. The plaza attracted people downtown throughout the summer, and Norton said he hopes to do some sort of winter festival in the coming months. It’s all in the service of making downtown a destination in Worcester.

“You get a couple of retailers, and it’s a bit of a herd mentality. More will follow,” he said. “That’s why Shrewsbury Street has been so successful, and hopefully, we’ll also become a destination.”

By Laura Finaldi